On the good news front it appears that the “but my house needs to breathe” argument is finally dead for most… Unfortunately though, a new “the wall assembly needs to breathe” &/or “dry out” are now becoming vogue. Shoot I am even guilty of using the term in the DER (Deep Energy Retrofit) Conversation piece I did. Folks a wall assembly, a house, or even the siding doesn’t need to breathe, it just needs to be able to dry out if it becomes wet. Ahh but even that is not fully correct as many in the Building Science field will attest “it all depends…”

On the good news front it appears that the “but my house needs to breathe” argument is finally dead for most… Unfortunately though, a new “the wall assembly needs to breathe” &/or “dry out” are now becoming vogue. Shoot I am even guilty of using the term in the DER (Deep Energy Retrofit) Conversation piece I did. Folks a wall assembly, a house, or even the siding doesn’t need to breathe, it just needs to be able to dry out if it becomes wet. Ahh but even that is not fully correct as many in the Building Science field will attest “it all depends…”

What does need to breathe?

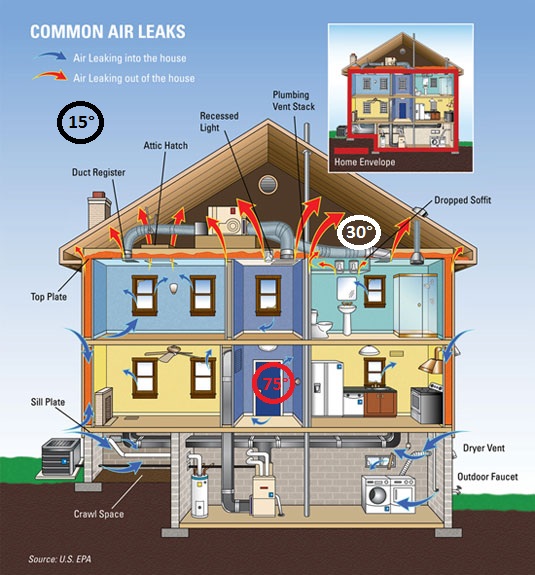

Just as a simple reminder, only humans and our pets in a house need to be able to breathe. The wall assembly’s, claddings, and even the house don’t need to which can become homes to many other creatures we don’t want in our house. Want to control mold & mildew responsible for breathing problems, rotted materials, etc… – eliminate the moisture or air & they can’t grow / thrive. Eliminating air leakage entirely is nearly impossible, but controlling the moisture isn’t. Quick Point – I am not saying you shouldn’t do everything possible to reduce unintended air flow (aka air leakage which is a big moisture transport itself) but getting it down to zero is nearly impossible.

Do all “assemblies” need to be kept dry?

In short no. If an assembly never gets wet, does it really need to dry out? Life & reality pretty much say that isn’t possible so you are told to avoid the dreaded moisture sandwich. While that is true for the most part, one can create an assembly with a “sandwich” as part of it and get away with it if can dry out to the exterior & interior. How about an assembly that never dries out?

One common example is concrete walls for a basement – if the concrete gets wet everything is still good. The catch though is you don’t want that moisture getting past especially if you are finishing the basement. That is one reason why we focus so much on grading, using a drainage plane, French drains, etc… With that, it takes at least a year for concrete to dry out and as the ground is essentially 100% saturated (thus keeping the material wet if it gets past), the walls still hold moisture in them and one reason why many basements are cool & sometimes have a musty smell to them. Needless to say dealing with this issue is an article onto itself, but don’t make the mistake of using plastic down there trying to control it…

Dry Out or Control Moisture?

For years Joe Lstiburek has said it the clearest – plan on moisture getting in & how to deal with it. While many would love to believe that the siding (or cladding) will keep all the moisture out of a structure we know that isn’t the case. Essentially the rule of thumb is that (whether it is brick, vinyl, Hardie Board, or wood) that 1% of the moisture an exterior wall is exposed to will get through. That is one reason why we use products like WRB’s, felt paper on roofs, etc… Unfortunately though, if to much vapor gets past that (all are vapor permeable) & forms back into water on the other side, it has no place to go but into the assembly especially if you are treating the “Tyvek” like an air barrier also (bottom taped).

For years Joe Lstiburek has said it the clearest – plan on moisture getting in & how to deal with it. While many would love to believe that the siding (or cladding) will keep all the moisture out of a structure we know that isn’t the case. Essentially the rule of thumb is that (whether it is brick, vinyl, Hardie Board, or wood) that 1% of the moisture an exterior wall is exposed to will get through. That is one reason why we use products like WRB’s, felt paper on roofs, etc… Unfortunately though, if to much vapor gets past that (all are vapor permeable) & forms back into water on the other side, it has no place to go but into the assembly especially if you are treating the “Tyvek” like an air barrier also (bottom taped).

Rules to consider:

Needless to say trying to cover all types of assemblies & climate zones is impossible in a piece like this, shoot many have written numerous books on just this subject. With that there are a few important rules to keep in mind. The first revolve are the building (whether new or remodeling) while the last few mainly revolve around the occupants. With that said, making smart choices up front can help minimize issues with those.

- Control bulk water – proper siding installation, drainage away from the building (gutters, ground, etc…)

- Allow for a path for moisture to escape – WRB’s with proper flashing details, rain screen details, hydro gap wrap, don’t caulk weep holes or bottom of siding

- Eliminate air leakage paths – the enemy is rarely diffusion (the reason most use plastic) but rather air leakage into & out of the building

- Choose the proper ventilation for your area – ERV/HRV rules, but there are other viable options

- Make sure all exhaust fans vent to the exterior – through the roof or gable (never the soffits)

- Control the interior moisture loads – use those fans, keep humidity levels down during the summer (40 – 50%) and winter (20 – 30%)

- Keep up on the maintenance – a well maintained house will not only keep problems at bay but also allow one to spot issues earlier